Residuum is defined as the residue, remainder, or rest of something. In chemistry it’s defined as a quantity or body of matter remaining after evaporation, combustion, or distillation. In “Residuum,” Will Miller and Toshi Onuki investigate memory’s selective bias toward unpleasant experience — how negative events can leave a lasting impression despite our best efforts to revise, edit, or sanitize those experiences. Here both artists present works that reference seminal childhood experiences. Miller’s recalls an olfactorily resonant first encounter with a rustic outhouse, and Onuki’s the confusion and chaos stirred by a perceived shortage of bathroom tissue.

Miller’s works engage memory, myth, nostalgia, and history — how they affect our collective consciousness and, ultimately, how we view ourselves. His Beef Jerky Outhouse series evokes the rough-hewn

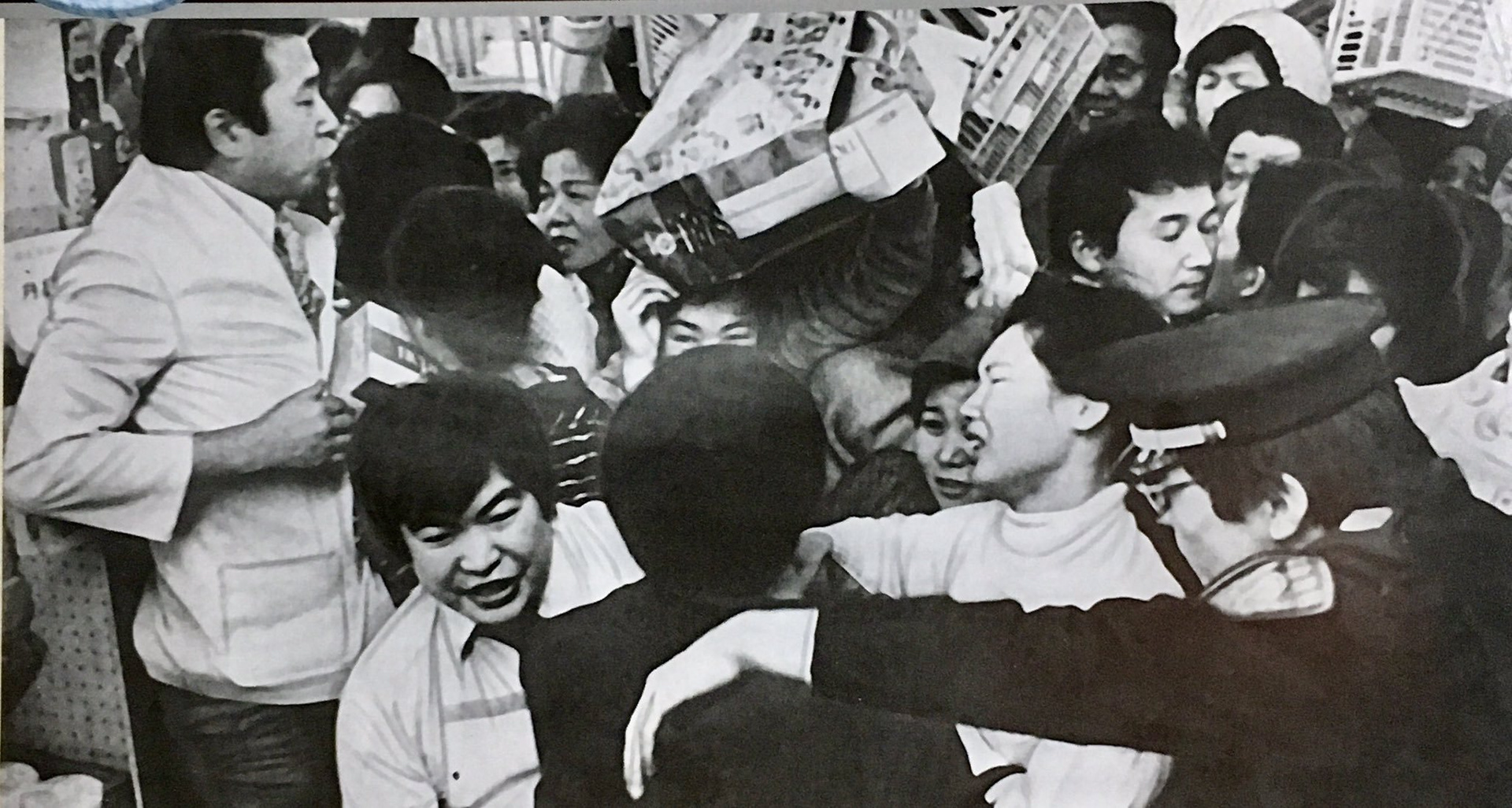

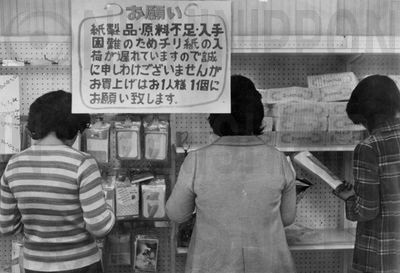

split-rail structures of yesteryear, the “necessary houses” of our pioneer past and former frontier. The sculptures acknowledge a yearning to escape to a more stable time before the turbulent flux of modernization, and a longing to recapture something we now know only in images and text. Of course today few of us have any real experience or connection to the hardships of that actual past. Perhaps Miller’s choice of an outhouse to conjure days of yore suggests that our glorious notions of those halcyon days are really full of it. What memories we have of our cultural past are like the structures here — enduring while in a constant state of decay. Both Miller and Onuki look critically at human consumption and waste. Miller recalls past systems, extinct in much of the world, while Onuki’s focus is on present systems and their future implications. Onuki’s sculpture Shit Happens is an immense, oversize toilet paper roll, composed of more than 1,000 rolls of bathroom tissue. Based on an actual event from his childhood, Shit Happens recalls Japan in the midst of the 1973 Middle East Oil Crisis when government officials warned of shortages of everyday consumer goods, including toilet paper. Panic and pandemonium ensued, as a hysterical Japanese public scrambled to buy as much toilet paper as possible. Viewing Onuki’s piece, one cannot help but think of all the delicate ecosystems threatened by human waste (the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is now a vortex of two islands east and west). The exaggerated scale of Shit Happens is both a powerful portent and a metaphor for a planet pushed by human consumption to a critical tipping point. Unforeseen shit will happen again, and as the earth reaches unsustainable levels of human development, it will happen with more frequency and severity. While confronting us with the magnitude of human consumption, Onuki’s piece also reminds us of our tenuous dependence on modern amenities.

split-rail structures of yesteryear, the “necessary houses” of our pioneer past and former frontier. The sculptures acknowledge a yearning to escape to a more stable time before the turbulent flux of modernization, and a longing to recapture something we now know only in images and text. Of course today few of us have any real experience or connection to the hardships of that actual past. Perhaps Miller’s choice of an outhouse to conjure days of yore suggests that our glorious notions of those halcyon days are really full of it. What memories we have of our cultural past are like the structures here — enduring while in a constant state of decay. Both Miller and Onuki look critically at human consumption and waste. Miller recalls past systems, extinct in much of the world, while Onuki’s focus is on present systems and their future implications. Onuki’s sculpture Shit Happens is an immense, oversize toilet paper roll, composed of more than 1,000 rolls of bathroom tissue. Based on an actual event from his childhood, Shit Happens recalls Japan in the midst of the 1973 Middle East Oil Crisis when government officials warned of shortages of everyday consumer goods, including toilet paper. Panic and pandemonium ensued, as a hysterical Japanese public scrambled to buy as much toilet paper as possible. Viewing Onuki’s piece, one cannot help but think of all the delicate ecosystems threatened by human waste (the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is now a vortex of two islands east and west). The exaggerated scale of Shit Happens is both a powerful portent and a metaphor for a planet pushed by human consumption to a critical tipping point. Unforeseen shit will happen again, and as the earth reaches unsustainable levels of human development, it will happen with more frequency and severity. While confronting us with the magnitude of human consumption, Onuki’s piece also reminds us of our tenuous dependence on modern amenities.

Inevitably, future generations will judge us not just for our accomplishments but also by the edifice of detritus — the residuum — we leave behind.